Our Horowhenua coastal community is on an estuary, at the mouth of the Waikawa Stream (we call it ‘the river’), which flows from the Tararua ranges. We live on the banks of the river, amongst wetlands, lakes, ponds, and streams, and beside a beautiful west coast beach. Many of us draw our household water from groundwater. Waikawa Beach Environment Group is made up of local people with a long standing connection to this place who have got together to restore and protect Waikawa’s coastal ecosystem so native flora and fauna can flourish. We are dedicated to preserving and restoring natural habitats, while fostering community engagement and promoting sustainable practices that will ensure the long-term health of our environment for future generations.

Many years of inadequate freshwater protection measures and management of natural and physical resources has failed to stop the decline of freshwater quality in the Waikawa catchment and degradation of our freshwater natural environments.

We live with the clear evidence, the state of our river, that we need strong policies and plans that protect freshwater. Government has blunted and stopped the 2020 freshwater changes that would have brought an improvement in our river. We fear that the proposed changes to the 2020 rules that being consulted on here will shift the balance even further away from one that would see our river and estuary recovering and protect the health for our lakes, ponds, wetlands and groundwater.

Fresh water and freshwater environments in the Waikawa Catchment

Freshwater monitoring by Horizons Regional Council shows that the water in the Waikawa River is on most water quality measures in excellent condition as it comes out of the Tararua Ranges, but by the time it reaches Waikawa Beach, it’s not looking so good. The measurements for the river go from the best in the region to some of the worst, and they mostly show that the trend is for worsening water quality.

Graph 1, below, shows the scores for different contaminants in the river measured by Horizons Regional Council at North Manakau Road near the bushline and at Huritini, just upstream from Waikawa Beach. ‘A’ is good, ‘E’ is very bad.

Once it leaves the bushline, the river runs through areas of dairying and dry stock farming, and some horticulture. Many farmers in the Waikawa catchment have taken measures to reduce contaminated run-off from their farms. Horizons Regional Council has partnered with landowners in the Waikawa Catchment over the past ten years to complete 10.5km of riparian fencing and plant 53,422 plants in riparian strips and to help stop erosion that contributes to sediment in the streams and river. But the water quality data clearly shows that run-off and leaching must be further reduced.

Recreation

For many years, the Waikawa River at Waikawa Beach has been a centre of community life. The river at the estuary has, in the past, been a popular swimming and picnic spot for locals and visitors.

For the last five years, the Waikawa river and estuary at Waikawa Beach have not been safe to swim in for more than half of the time during summer.

The community boat day has been an annual New Year’s Day event since 1978. The weather was great the last two New Year’s Days, but Boat Day was cancelled because the river water was unsafe for swimming. The measured E-coli levels showed an unacceptably high risk of catching skin, eye, and ear infections from contact with the water, and stomach upsets (including really bad stuff like campylobacter) from ingesting it.

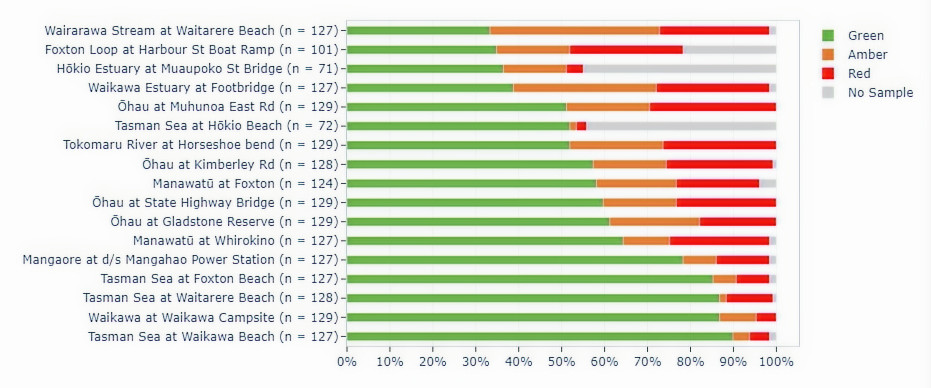

Graph 2 is Horizons Regional Council water testing data from the last five summers. It shows the ‘swimability’ of the regions’ rivers at different locations. The Waikawa water near the bushline (at Waikawa campsite) goes from some of the best in the Horowhenua to some of the worst by the time it reaches the Waikawa Beach footbridge.

Green means a low risk of illness. Orange means that caution is advised, there is an elevated risk to health, and young children, the elderly or people with health conditions may be at an increased risk of illness. Red means there is a high risk of illness from swimming.

LAWA data shows that at Huritini, just upstream from the Waikawa Beach settlement, the e-coli levels for the past five years are amongst the worst 25% in the country, and that over the past five years, the e-coli results show that the situation is worsening.

Testing of e-coli in the river shows that it mostly comes from livestock waste, with some avian source, and no evidence of human source.

Degradation of the Waikawa River Ecology and impact on food gathering

Insect, bug, and fish life in the river is struggling because of the poor water quality. At Huritini, the river has tested in the bottom 25% of all rivers in NZ for biodiversity, using eDNA analysis. eDNA assesses river life by analysing water samples for traces of DNA released by organisms in the water, providing a snapshot of the river's biodiversity.

Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (LAWA) reporting on the macroinvertebrate data for the Waikawa River at Huritini shows "severe loss of ecological integrity".

The estuary is not healthy. Testing has found that it is "under pressure" and "expressing signs of eutrophication". Eutrophication begins with loading nutrients like phosphates and nitrogens to estuaries and coastal waters which then cause harmful algal blooms, dead zones, and kill fish.

The loss of bugs and insects in the river has effects up through the food chain. As well as showing that the natural environment is sick, this loss impacts directly on people by effecting whitebaiting and eeling in the river, and gathering water cress in the tributary streams. For many years people caught flounder and kahawai in the estuary, but not that much anymore.

Groundwater

There is no publicly available information about ground water quality at Waikawa Beach. Private testing of some Waikawa Beach settlement’s groundwater has shown NO3-N contamination at levels below the maximum acceptable value (MAV) of 11.3 g/m3 No3-N, but one result came back at 9.39 g/m3 No3-N. Several dwellings in the settlement are dependent for household water on bores and sandtraps.

There is increasing evidence of risks to the health of people dependent on NO3-N contaminated ground water for their homes. New Zealand’s current maximum acceptable value (MAV) for nitrate levels in drinking water is 11.3 mg NO3-N/L (mg/L), based on preventing methemoglobinemia in infants (MoH, 2018). Evidence is now emerging that there is a statistically significant increase in the risk of developing colorectal cancer in adults exposed long term to drinking water with nitrate concentrations as low as 0.87 mg/L (Joy et al., 2022; Schullehner et al., 2018; Temkin et al., 2019). The chance of a preterm birth also increases by 47% when exposed long term to drinking water with nitrate concentrations above 5 mg/L (Chambers et al., 2021).

The level of nitrate run-off from into Waikawa catchment waterways is high. The LAWA data on nitrate levels over the past five years in the Waikawa River at Huritini, just upstream from the footbridge, are amongst the worst in New Zealand.

Ground water nitrate and phosphate contamination can show up in ponds and lakes and streams as water weed overgrowth and algal blooms. Many of the groundwater fed ponds and lakes around Waikawa Beach have these problems.

Wetlands

The Waikawa catchment once had huge wetlands, but most of these have been drained for farming. Very few of the remnant wetlands are legally protected. We need to protect and care for the remnant wetland environments we have left. Wetlands provide habitats for the game fowl and eels that people in our community hunt for food. Our remnant wetlands are where some of New Zealand’s most endangered species live. There are a handful of farmers in the Waikawa catchment who have done great work fencing and protecting wetlands and lakes, such as Lake Huritini and the Camerons at the south end of Waikawa Beach. They have and provided a rare safe habitat for Australasian Bitterns (matuku hūrepo). There are less than a 1000 of these birds left in the wild.

Our view on the proposed freshwater changes

Part 2.1 Rebalancing freshwater management through multiple objectives and Part 2.2 Rebalancing Te Mana o Te Wai

Freshwater and freshwater natural environments in the Waikawa River catchment demonstrably need more protection, not less. Previous versions of the NPS-FM and Te Mana o Te Wai have not been strong enough to prevent the continued decline in the freshwater quality in the Waikawa River catchment.

The NPS-FM 2020 and Te Mana o Te Wai 2020, as they stand, will drive the changes that we need to secure clean fresh water for our community and environment. We are bitterly disappointed at Government’s actions in stopping our local Regional Councils from implementing the freshwater management plans they have developed under the NPS-FM-2020 and Te Mana o Te Wai.

Protections for freshwater in our river catchment have already reduced due to the interregnum we now have between the revoked Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020 and the delayed implementation of regional councils new freshwater management plans.

Now the Government is proposing changes to weaken the NPS-FM 2020 and Te Mana o te Wai (in the Ministry for the Environment, Package 3: Freshwater – Discussion document, 2025) and significantly compromise the resource management protection of our fresh water quality. We are opposed to these proposed changes.

We support keeping the existing single objective for managing natural and physical resources as laid out in Te Mana o te Wai 2020 and the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020:

(a) first, the health and well-being of water bodies and freshwater ecosystems

(b) second, the health needs of people (such as drinking water)

(c) third, the ability of people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being, now and in the future.

We oppose the Government’s proposed changes to this objective to "rebalance" the competing needs of food production and protection of freshwater and provide an enduring framework for freshwater protection by introducing "multiple objectives" that would deprioritise protecting freshwater, as both unnecessary and damaging.

What the discussion document calls 'rebalancing' "freshwater management through multiple objectives" means in reality that the health of our river, lakes, ponds, streams, wetlands, and groundwater will be deprioritised and further harmed.

The change proposals to introduce new freshwater objectives and diminish or remove Te Mana o Te Wai, will water down, weaken, and muddle regional councils’ protection of freshwater in their resource management plans, rules, and consenting decisions.

We reject the false dichotomy of food production vs freshwater protection that lies at the base of these proposed changes. The 2020 freshwater rules that are now under attack provide the balance we need to drive uptake of food production freshwater protection practices on the ground that minimise contamination of freshwater. Food production industries must not continue to be protected and enabled to externalise the costs of fresh water contamination. It is not acceptable to leave Waikawa Beach and other communities and our natural environment to bear the effects of worsening water quality and the degradation of freshwater environments that will result from the proposed changes.

These proposed changes, which will allow ongoing unacceptable levels of freshwater degradation and polluting industries to continue to externalise the costs of that pollution, will not produce the enduring freshwater resource management system the Government and industries say they want.The Government may regard the many hours of time from the community and regional council resources (ratepayers’ money) invested in operationalising the NPS-FM 2020 as a sunk cost. We regard it as an investment that will be realised when these shortsighted proposed changes are reversed. Nor will these proposed changes support a sustainable and therefore enduring food production system. Our descendants will not thank us for choosing to further sacrifice the natural environment for short term economic gain.

Full operationalisation of the existing single objective for managing natural and physical resources, as laid out in Te Mana o te Wai 2020 and the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020, is our best option for improving the freshwater and rehabilitating freshwater natural environments in the Waikawa River catchment upon which the wellbeing of our human communities ultimately depend.

Part 2.3: Providing flexibility in the National Objectives Framework

The Government change proposals will gut the integrity of the freshwater national objectives framework that allows comparisons across regions, and sets measurable targets and bottom lines and triggers meaningful Regional Council action to protect freshwater. The existing 2020 rules give Regional Councils significant flexibility to implement them in ways that suit their catchments. What Government condemns as inflexibility in the national direction in the 2020 policies and rules is what prevents councils or communities choosing to actively continue to degrade their waterways, lakes, streams, ponds, and wetlands or to have pollution that is worse than the bottom lines set out in the national policy and rules.

We want the Government to keep the National Objectives Framework and national bottom lines to protect our Waikawa Beach environment and community against polluting interests which have more resources than we do to influence local government.

We support retaining the existing National Objectives Framework. Having a clear and consistent framework and system of monitoring fresh water in the Waikawa River and making data publicly available lets us see objectively how much e-coli and other contaminants are in our river, and how we compare with other rivers. This, combined with other research, helps us to know how healthy our river is and whether it is getting better, or whether the Regional Council needs to move on water contaminating activity in our catchment.

Proposals affecting wetlands

Part 2.6 "Simplifying the wetlands provisions"

The Government seeks a "clearer more workable definition of wetlands", by, amongst other proposals, "removing the pasture exclusion in the definition of a natural inland wetland" in the National Policy Statement – Freshwater.

We are opposed to this proposal. It would mean that there is no clear way to distinguish between pasture and wetland to protect the wetland in cases where the existence or boundary of the wetland is contested. A definitional distinction is needed. A scientific-evidence based alternative must be agreed before the existing pasture exclusion is removed. To do otherwise risks further wetland loss, particularly where it is habitat for endangered species. This is especially important because of the effect of the proposed changes to the Resource Management (Stock Exclusion) Regulations 2020 that are amongst the proposals discussed in the Primary Sector Discussion Document.

We are opposed to the proposal to remove the requirement for councils to map natural inland wetlands within 10 years. The catchment we are submitting about once had large areas of wetland. Only remnants remain to provide habitat to endangered species and very few of these are protected. Without active and rapid mapping, remnant wetlands supporting endangered species are at risk of degradation and destruction.

The impact of the above proposals is magnified by the proposal to amend 17 of the Resource Management (Stock Exclusion) Regulations 2020 (2.6 in the Primary Sector Discussion Document) - the proposal is to amend the requirement that all stock must be excluded from any natural wetlands that support a population of threatened species, so that it would not apply to non-intensively grazed beef cattle and deer.

.

The effect of this change is that:

-

The area in which farmers will be required to fence stock out of wetlands that support a population of endangered species will be massively reduced. Officials have advised Ministers that the change would mean that wetlands in more than 2.5 million hectares of land used for grazing cattle and deer would no longer be protected from those livestock.

-

The areas where farmers will still be required to fence stock out of wetlands, ie, where intensive grazing (as per the definition in the regulation) does occur, are unlikely to contain wetlands.

Fencing stock out of wetlands is important because livestock grazing and trampling harms the ecosystem of wetlands that are habitats for endangered plants and animals.

The Waikawa catchment had huge wetlands, but most of these have been drained for farming. We need to protect and care for the remnant wetland environments we have left. Our endangered remnant wetlands are where some of our most endangered species live. Some farmers in the Waikawa catchment have done good work fencing and protecting wetlands and lakes, and providing a home for Australasian Bitterns (matuku hūrepo). There are less than a 1000 of these birds left. A very small proportion of the remnant wetlands in our catchment are protected. Without NPS-FM 2020 requirements to map and provisions to distinguish wetlands from pasture, and regulation to exclude livestock from wetlands, we risk the loss of most of the remaining wetland ecosystems in the Waikawa catchment.

“Simplifying the fish passage regulations”

The fish passage regulations are there to make sure that migratory fish can get up and down rivers, and to ensure that fish can move easily through their habitat to feed and have good fish lives.

We oppose any changes to the fish passage regulations that will further degrade the habitat of native fish. 76% of our native fish are threatened with or at risk of extinction. A recent analysis of insect and fish life detected in the Waikawa River shows that the fish are not doing well. The Waikawa River gained a rating of ‘poor’.

Co-benefits of regulations should also be taken into account, noting that the Ministry for the Environment’s Regulatory Impact Statement also says existing rules for fish passage “are based on best practice standards developed in the 2018 version of the Guidelines and, if met, the structure is unlikely to impede fish passage. These structures are likely to be more resilient to storm events due to their ability to handle high flow rates (Gillespie et al., 2014)”

Relaxing the rules for applying synthetic nitrogen Fertiliser

Government is proposing to weaken the rules that control and monitor how much nitrogen fertiliser farmers can put on the grazed area of their farms. We know that nitrogen leaching and farms livestock and from fertiliser does harm to the ecology of our rivers, streams lakes, ponds, and wetlands, and groundwater.

LAWA data on nitrate levels over the past five years in the Waikawa river at Huritini, just upstream from the Waikawa Beach footbridge, are amongst the worst in New Zealand. The good news is that the trend is showing an improvement. It could be a sign that the regulations controlling nitrogen fertiliser use are working.

It is too early to relax regulation limiting use of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser.

We oppose this proposal.

People in communities with nitrogen contaminated ground water pay the price in known negative impacts on health, and in the costs of avoiding these, such as having to install and run and maintain rainwater storage system, and buying in water in dry summers.

In summary

We oppose the change proposals made in the Ministry for the Environment, Package 3: Freshwater – Discussion document, 2025.

The consultation document says that the "Government wants to remove further regulations where the benefits of the rules do not outweigh the costs for the primary sector". The suggested changes to the regulations leaves too much of the say in this equation to the primary sector itself. We have regulations to balance competing interests and ensure that the activities of one party (the agricultural and horticultural sectors) do not harm another (the freshwater that is a resource for us all and is fundamental to the health of our natural environment).

We strongly support:

-

retaining the existing NPS-FM 2020 and Te Mana o Te Wai 2020;

-

immediately removing central Government impediments preventing Regional Councils from bringing their NPS-FM 2020 and Te Mana o Te Wai 2020 freshwater management plans into effect;

-

reinstating the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020 that were revoked in 2024 to remain in force until all regional councils have operating freshwater management plans that are consistent with NPS-FM 2020 and Te Mana o Te Wai.

We oppose proposals that will

-

gut the system for monitoring and setting bottom lines on contaminants in our freshwater;

-

in effect remove protections from wetlands;

-

change the fish passage regulations in anyway further degrade the habitat of native fish;

-

relax the rules for applying synthetic nitrogen fertiliser.

We recognise and applaud that many farmers have taken steps to protect freshwater around their farms. We support Government furthering this by:

-

maintaining financial assistance to farmers in implementing measures under the 2020 rules to protect freshwater, including renewing funding support for fencing and riparian planting,

-

restoring full implementation of the 2020 Freshwater Farm Plans with proactive support and external audit and oversight that is independent from the agricultural and horticultural industries;

-

encouraging formation of catchment groups, including establishing a group in the Waikawa Stream (Horowhenua) catchment.

References

Chambers, T., Wilson, N., Hales, S., & Baker, M. (2021). Nitrate contamination in drinking water and adverse birth outcomes: emerging evidence is concerning for NZ. Otago University: Public Health Expert.

https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/nitrate-contamination-in-drinking-water-and-adverse-birth-outcomes-emerging-evidence-is-concerning-for-nz/

Joy, M. (2022, May 30). 11,000 litres of water to make one litre of milk? New questions about the freshwater impact on NZ dairy farming. The Conversation.

https://theconversation.com/11-000-litres-of-water-to-make-one-litre-of-milk-new-questions-about-the-freshwater-impact-of-nz-dairy-farming-183806

Ministry of Health (MoH). (2018). Drinking Water Standards for New Zealand.

https://www.taumataarowai.govt.nz/for-water-suppliers/current-drinking-water-standards/

Schullehner, J., Sigsgaard, T., Hansen, B., Thygesen, M., & Pedersen, C. B. (2018). Nitrate in drinking water and colorectal cancer risk: A nationwide population-based cohort study. International Journal of Cancer, 143(1), 73–79.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31306

Temkin, A., Evans, S., Manidis, T., Campbell, C., & Naidenko, O. V. (2019). Exposure-based assessment and economic valuation of adverse birth outcomes and cancer risk due to nitrate in United States drinking water. Environmental Research, 176.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.04.009